When I was elected San Francisco’s Sheriff in 1980, the official duty I most dreaded was civil evictions. Jails, I understood: a man or woman gets arrested for criminal probable cause and gets locked up. The prisoner’s care is then the responsibility of the government. Housing, food, medical and security are all provided. But with an eviction, when the rent isn’t paid or the lease ends, the whole family gets evicted. Admittedly, there is a court proceeding and a certain amount of notice, but when the eviction is ordered, the whole family loses their home. Usually, no crime has been committed. The most common reason for an eviction is the failure to pay rent and the most common reason for failing to pay the rent is not having enough money.

In California, only the Sheriff can enforce an eviction order. Not the police; not the Housing Authority; and certainly not the landlord. In San Francisco there are thousands of evictions each year.

In reality, by the time the Sheriff gets the eviction order from the court, there is very little recourse for the tenant. The eviction is generally inevitable and most evictions are fairly routine. In days past and in other jurisdictions, a tenant’s belongings were summarily moved to the sidewalk, but California law stopped that practice long ago. These days the deputy sheriff merely makes sure that no one continues to occupy the apartment or house and sees that the locks are changed. California law requires the landlord to either move and store any remaining property or to leave the property in the unit for a number of days, and in either case, give the tenant the opportunity to retrieve it.

Most of the time, when the deputy sheriff arrives with the locksmith, the unit is vacant, a check is made to make sure everyone has vacated, the locks are changed and the matter is over. But many, many evictions are not routine.

Deputies oftentimes find an apartment totally trashed or with pizza boxes or other nastier debris stacked to the ceiling. On several occasions during my time as Sheriff, deputies entered the apartment only to discover a suicide. Once when Senior Deputy Dave Fambrini gained entry during an eviction he encountered a man sitting in a pool of gasoline holding a lighted candle. Fambrini managed to talk the situation down to a safe resolution.

Because so many evictions were sad cases, we applied for a federal grant and created a Sheriff’s Eviction Assistance Unit. The “angle” was that all of the staff doing the social work for the new Unit were senior citizens. We employed ten senior citizens who worked with the deputized staff to provide services and referrals to people facing evictions. It was already standard practice for the deputy sheriffs who were posting the eviction notices to report back any potentially dangerous situations, such as aggressive dogs or particularly angry tenants. To this we added a requirement that they were to report elder tenants, tenants with young children, persons with obvious mental incapacities or other situations where sympathetic social workers might make everything go more smoothly. Then, prior to the eviction date, the Eviction Assistance staff would visit the tenants, explain that the court order was at the inevitable stage and ask if assistance was needed to find new housing, help in moving or provide any other help that may be needed. The Eviction Assistance staff then worked with social services groups like Catholic Social Services, Salvation Army, the Jewish Community Center and local churches to help the tenant move to a new situation. Many hundreds of tenants were helped in this manner and landlords appreciated that the eviction was conflict free. After several years, grant funding came to an end and the project was reduced to two deputy sheriffs who largely served the same function.

Evictions could also be quite personal. During the ten years I lived in Bernal Heights, my wife Beverly and I became friends with our neighbors on both sides of our house. We exchanged cakes and cookies and black-eyed peas on New Year’s Day. Both neighbors ended up being evicted by my deputies.

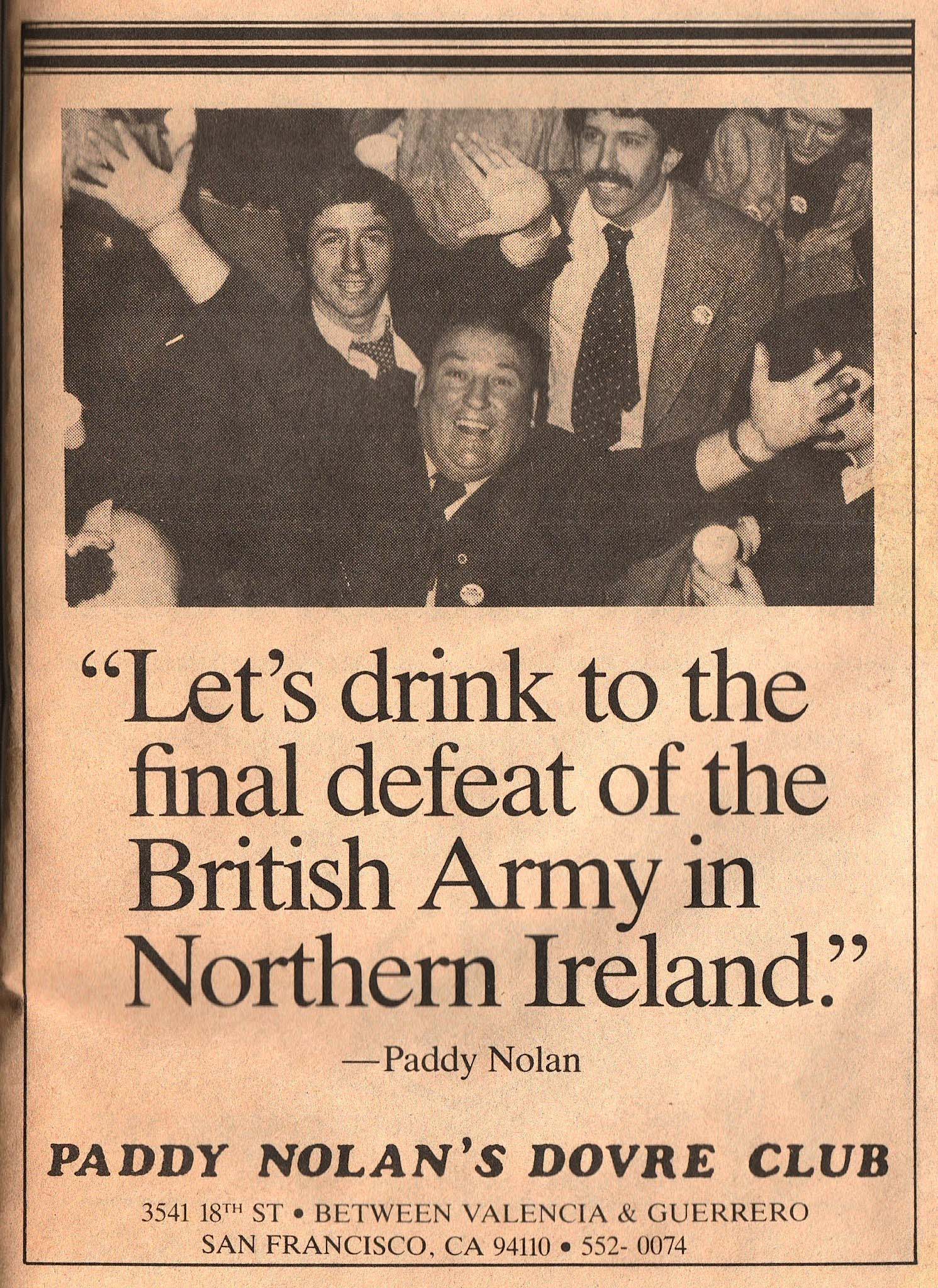

Paddy Nolan, center, celebrates St. Patrick's Day. His favorite toast was posted on a large sign above the Dovre Club door so that it was the last thing you saw as you left the bar.

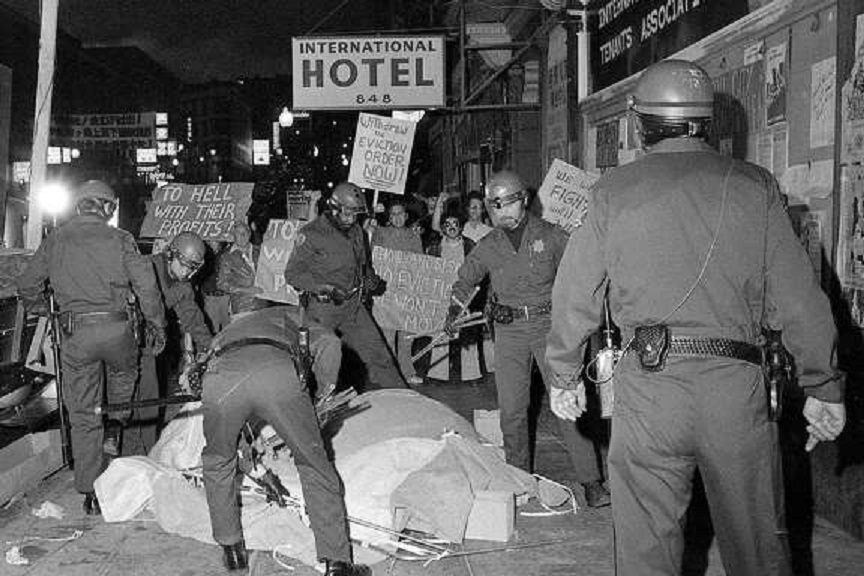

The biggest and most contentious eviction in Sheriff’s Department’s history was in 1977 when a hotel in Chinatown, the International Hotel, became an infamous political football. The hotel was a low-cost home to scores of elderly Filipino and Chinese tenants. An international corporation bought the site with the intent to tear down the structure and erect a high-rise building. Sheriff Richard Hongisto first refused to honor the court order which resulted in him being found in criminal contempt of court and sentenced to five days in jail, which he served in San Mateo County’s jail. After the jail term, the Sheriff and the San Francisco Police combined forces to break through the demonstrators at the International Hotel, vacate the building and complete the eviction. On the day of the eviction there were an estimated 3,000 demonstrators surrounding the building.

Not all evictions are characterized by anguish or sadness. In 1998 Dennis Peron, the head honcho of the Cannabis Buyers Club, begged me to evict him and his organization.

I had known Dennis Peron for many years. He was a familiar figure in San Francisco politics, primarily as the most visible proponent for the legalization of marijuana in California. In 1991 Dennis campaigned in San Francisco for Proposition P, a local resolution calling on the state to allow medical marijuana. It received 79% approval. I was up for election that same year, so Dennis and I spent a lot of time together on the campaign trail waiting for our turn to speak while seeking endorsements from various groups.

After unsuccessfully trying a variety of approaches to change state law, Peron was victorious with the passage of Proposition 215, California’s medical marijuana initiative. I was the only Sheriff in the state to endorse Proposition 215, and Dennis campaigned for months throughout the State at his own peril amid official and public opposition. He was even arrested by the Bureau of Narcotics Enforcement a month before the election.

Dennis Peron in the headquarters of his 1998 Republican primary run for Governor of California, located in the basement of the Cannabis Buyers Club on Market Street. Peron coined the phrase "All cannabis use is medicinal".

The Cannabis Buyers Club was located in a five-story building only three blocks from City Hall. The owner of the building, a Mr. Zack, was an elderly man whose wife had died of cancer. He gave Dennis a lease for the Club when no one else would. In the basement of the building was the “Peron for Governor” office. Dennis was running in the 1998 Republican gubernatorial primary against State Attorney General Dan Lungren, whose staff included the Bureau of Narcotics Enforcement.

The Buyers Club was tolerated by the San Francisco Police Department, but was in the crosshairs of the California State Bureau of Narcotic Enforcement. After about a year in operation, Mr. Zack terminated the lease and initiated eviction proceedings. It was widely believed that he was threatened by the State with confiscation of the building if he continued to allow operation of the Club in his property.

The eviction was fought in court, but a local judge ultimately issued the eviction. It was an unusual order. While the local Sheriff is responsible for enforcing court ordered evictions, this particular order came with the proviso: “should local authorities decline to perform the eviction, the State may act.”

I certainly was not looking forward to evicting the Club. There was a great deal of media following the drama and there were rumors of barricades and demonstrations by the Club’s supporters. Dennis didn’t help the matter by going on television and saying that if the State guys were coming in their military gear, “it will be another Waco.” The reference was to a disastrous FBI siege of the Branch Davidian compound near Waco, Texas in 1993, at which 76 people died.

I was being pressured by state, local and national television and radio reporters to give them details about date and time of the eviction. I was also being pressured by local political partisans urging me to refuse to perform the eviction. So, I was relieved when I read the court order and saw that I was not being forced to either perform the eviction or defy the court, the latter of which was never a real option in my opinion.

A day after the court order was issued, I got a phone call from Dennis. I greeted him and said, “Good news, Dennis. I’m not going to evict you after all.” Dennis almost wailed, “No, Mike! You’ve got to evict me! If those state guys do it, they are going to kick my ass!” Dennis said he would be fully cooperative, particularly if I gave him three days “to get the place cleaned up.” We came to an agreement.

The next day I got a call from an agent from the Bureau of Narcotics Enforcement.

“Just heard that the judge issued the order, is that right? Well, I’m supposed to call and ask whether your department intends to, you know….”

“Enforce the order?,” I asked.

“Well, yeah,” the agent replied.

“Yes,” I told him.

“If I can ask, how come the change of… well, not attitude, but position?,” he wanted to know.

I told him, “I figured fewer people were likely to get hurt if we did it rather than your guys.”

“Well, you are probably right there. What can we do to be of assistance?”

“Nothing”, I said. “Just step back and stay out of the way. And give my regards to the Attorney General.”

The next Monday, April 20, 1998 I had our staff ready to go with video cameras, traffic cones, barricades, a locksmith and a truck to haul away anything that might look illegal. I walked the several blocks over there from City Hall and as I turned onto Market Street I saw about 50 people near the front door. As I got closer and prepared myself to confront protestors, I saw that the crowd was not protestors but reporters and camera crews. I waded through the media and went through the open front door. The building had been pretty much emptied out, although Dennis left a bunch of sick looking marijuana plants and a couple of 1930’s scales which made for good television when the deputies carried them out to the truck.

The process of searching the building’s five floors and basement took about three hours. There were no sightings of either Dennis Peron or the State Bureau of Narcotics Enforcement.

Postscript: Neither Dennis Peron nor Dan Lungren ever became California’s governor.

Next: County Jail Keys: How the Five Keys Charter School Got its Name